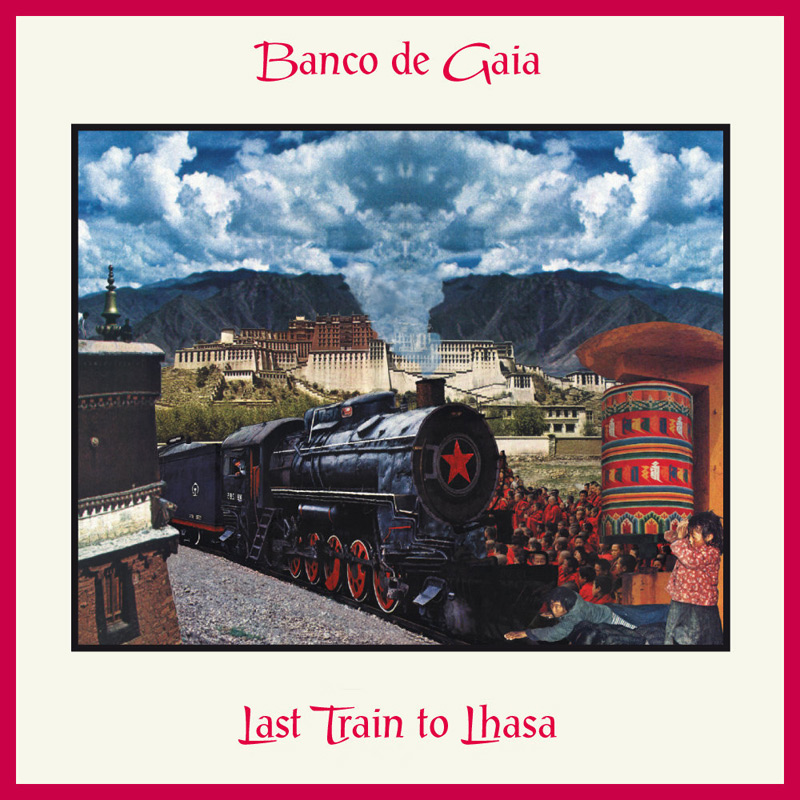

Banco de Gaia — Last train to Lhasa. Story behind the album

“Last train to Lhasa—is not a concept album. The album’s not particularly written about Tibet—there’s nothing about Tibetan music at all apart from there are some Tibetan samples in a couple of tracks.” explains Toby Marks, better known as Banco de Gaia. “The album on whole had no concept, no plan. I just went in and wrote the individual tunes as I went along. The Tibetan thing was pure chance. I was working on this track which sampled a train, and couldn’t think what to call it. My wife said How about Last train to Lhasa? [The capital of Tibet] and I was like That’s cool, I like that. I really liked the sound of Last train to Lhasa as a name, it sounded really catchy, so we used it for the whole album. I didn’t want to write political songs or chant slogans but I thought the album cover would give me a chance to spread awareness and use the attention the album would get for a good cause. I was in the privileged position of having the attention of quite a large number of people so I wanted to point their attention to something that I felt was really important, and just might help the Tibetans’ cause a little.” Toby contacted the Tibetan Independence Movement and received a collage picture for the front cover and a text for the spread.

“I used to read a lot of books about Buddhism and mysticism and sort of magics and religions and so on,” recalled Toby. “Tibet always seemed to be portrayed as this really special, pure spiritual culture which to an extent may be idealized but as far as I could gather really was a very unique place.”