Brian Eno — Thursday Afternoon. Story behind the album with one 60-minutes track

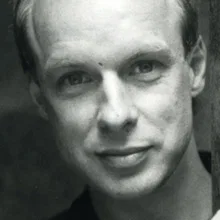

One day in the first half of the 1980s, Brian Eno, who had moved to New York, wanted to shoot the charming sky of Manhattan. He took out his film video camera and for about four days filmed the movement of clouds outside the window. Since there was no tripod at hand, Brian simply put the camera on its side.

Brian Eno

Brian Eno

Because of this, the picture on the TV was vertical and, without thinking twice, Eno turned the TV on its side. The slowly floating clouds reminded him of the slowly floating music, and the vertically placed TV immediately stopped being a TV—now it looked like a canvas that slowly came alive. In addition, the sun burned out the colour filter of the camera, which made the colours on the video look slightly different. This delighted Eno: “It was a beautiful camera. It responded to light and colour in a way that no other camera I’ve ever seen can do. So I had a unique paintbrush really and I worked with that for a long time. I could set it at a level of light sensitivity where very slight changes in the amount of light, the brightness of the light, translated into very powerful colour changes.”