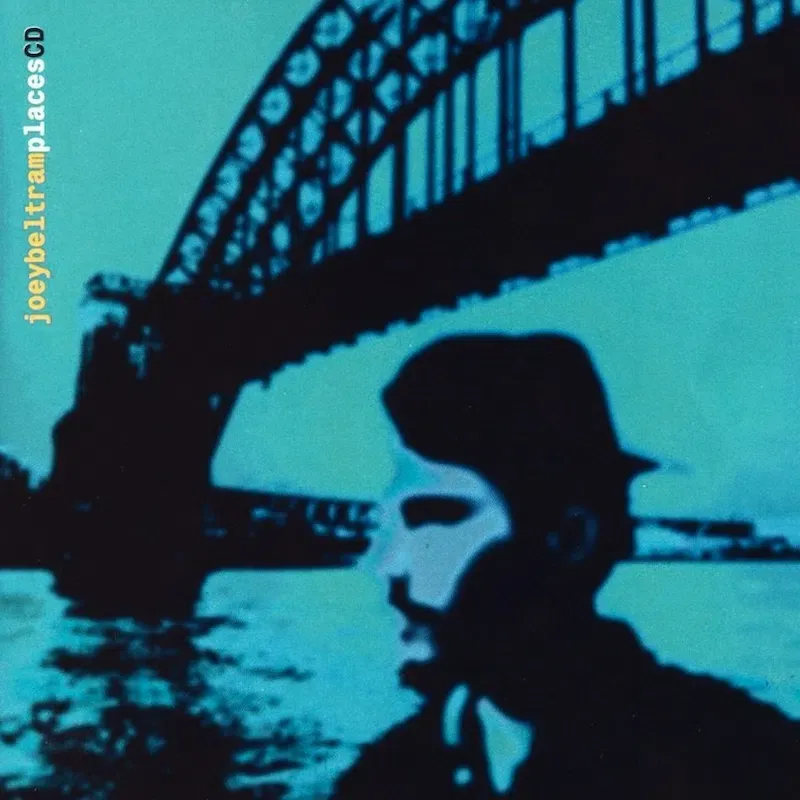

Joey Beltram — Places. Story behind the album. Track by track guide

As a DJ I was playing out a lot back then, so that’s what I wanted to make my music for. There were a lot of albums that came out that just had one or two tracks made for the dancefloor. Everyone was trying to make artist albums with little artsy tracks thrown in, trying to show versatility. I remember wanting to come out with an album that was just bangers. Every track was made for me; what I’d wanna play. I wanted eight to ten tracks of just

I’d be riding the gear

in real-time. I was doing all those parameter changes with the resonance and cutoff live. I was like an octopus, with one hand on this bit of kit, and the other on the other side of the studio on a different keyboard, moving things as I needed to.

Places was, like, all 133 bpm or whatever the speed of techno was back then. It was like buying eight 12″ records, which is what I wanted, and why I think people dug it.