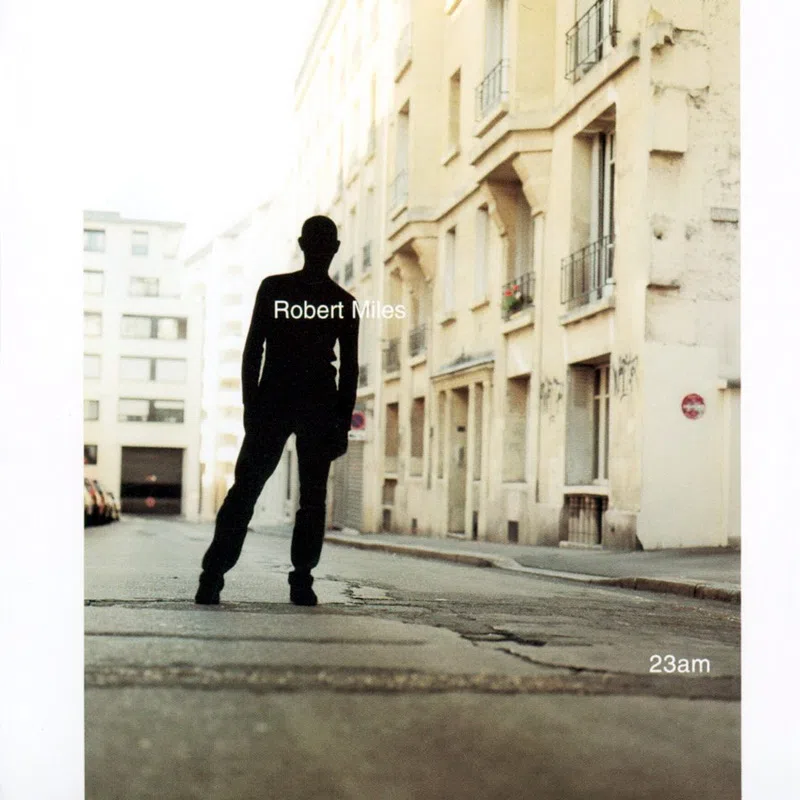

Robert Miles — 23 am. Story behind the album

Twenty years ago the 23 am album came out. And in this May Robert Miles passed away. This brings me once again to the thought of the legacy and the memories that we leave. Artists leave things they lived for: music, films, books, and paintings. Artists leave this world, but their vision carries on influencing others. And, perhaps, this is the meaning of their

The first album, recorded with minimal means, enjoyed unimaginable success and, for a short time, made Miles one of the wealthiest people in the dance scene. Dream house and its components were a sensual reminder of the shortness of life and fragility of people. Disfigured by imitators, the style was soon dethroned

by drum and bass, trip hop and trance music, which were rapidly entering the UK. This was the bundle which Miles planned to experiment with on his second album.