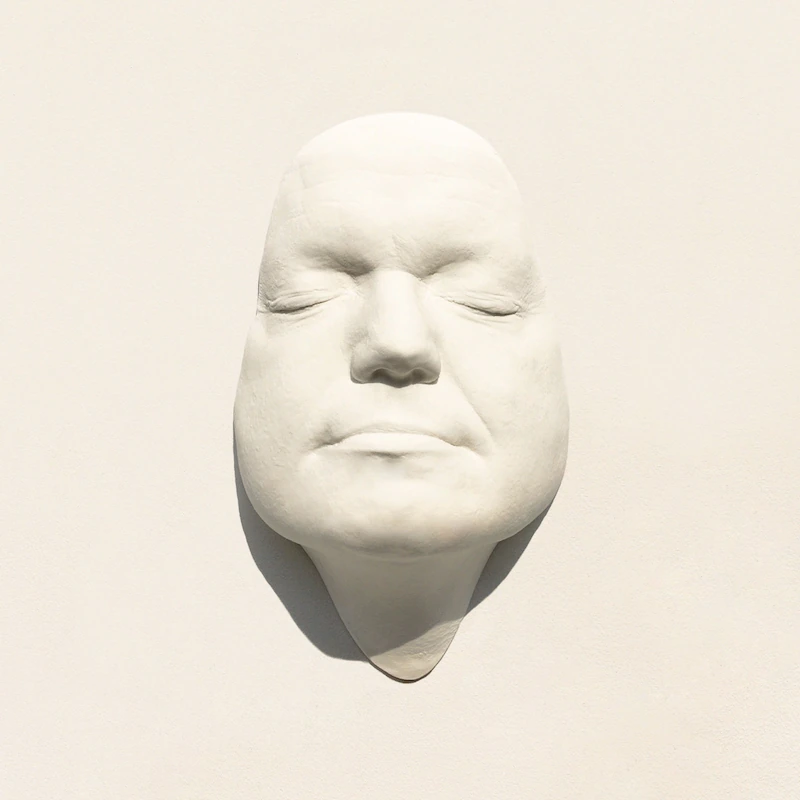

St Germain. Third revival

Almost all the texts about St Germain that have been written over the last three years begin with this question: where was he during all this time? It’s a reasonable question that has been asked on special forums everywhere in the world. A person who released music for a whole decade and sold millions of copies and received platinum certifications can’t just disappear. Only if he was very confident and understood that it was impossible to get any higher. There were rumours that he had finally retired on a distant island where he could wind surf as much as he wanted.

In reality, the reason for that was